Five years ago, coming down to Kashmir from the barren slopes of Ladakh was like stumbling upon Paradise. The green tall trees soothed my eyes after the stark high slopes of hard rock. The sound of rushing water and the humming of bees, as they swung lazily over the masses of flowers, was sweet music indeed.

The land of infinite charm was calling me again

Srinagar was busy and quietly occupied with the business of loading the rich and juicy fruits that had been fetched from the many orchards around the countryside into trucks that would carry them away to the rest of the country. And though we briefly saw the Dal Lake only after nightfall, its presence was tangible and alive at the edge of the road that the traffic moved upon.

We stayed at a friend’s friend’s house, at the edge of the old city. And I found long walks in the grasslands close by, which skirted humble huts and makeshift shops, a great way to spend my evenings. I would return in time for a warm meal and to layer myself in a warmer sweater, as the cold descended from the nearby mountains and hung with the mist till the morning.

The memories stayed. And despite the news of bandhs and curfews, firings and all the rest of the turmoil that only humans can cause, I could only think of Srinagar as a land of infinite charm and beauty.

Which is why, when a friend asked me to accompany her to Srinagar while she went to check on her new house still being built, I agreed with alacrity. Making the most of not being on the nine-to-five treadmill, I packed my bags and bid goodbye to my own home for the next fortnight.

Srinagar or Mumbai?

The first disappointment came when we reached the house. I had been warned that we would be staying in what was practically an outhouse, as the big house was yet to be completed; but I was more than game. The disappointment was in the fact that the house was nowhere near Dal Lake, but in one of the new developed areas, close to the airport. We were thus situated on the high end of a slope, surrounded by new chalet-like homes that dotted the winding road down to the arterial road. But that meant there was nowhere to walk. No stretching wilderness, no green, flower-decked fields.

However, far away, the snow gleamed on the mountains and there was a stretch of tall poplars and willows waving in the breeze, and I comforted myself with the sight. Every city, I told myself, has to stretch itself to accommodate new areas of development. Why should Srinagar be an exception?

Every city, I told myself, has to stretch itself to accommodate new areas of development. Why should Srinagar be an exception?

But on my first trip to the centre of town, I realised just how much the city had changed: traffic jams, as two-lane traffic was funnelled into a half lane, which was cordoned off to complete flyover work; flyovers bent over roads that were once tree-lined, but now stood bare and dusty in the afternoon sun; dust coated, the sides of the roads and the houses that stood alongside looked sad and neglected, crying out for care and a lick of fresh paint. I could see none of the cheerful joyousness that symbolised a fresh green valley was in evidence. By evening, a splatter of rain did its worst. Like any other city, where roads have been paved to block the natural seepage of water into the soil, Srinagar’s roads were quickly flooded. Traffic came to a standstill, tempers flared, words flew across car windows, and I wondered why I had travelled so far to revisit a bad evening drive, like back home in Mumbai.

Splendid serendipity

The days were still very warm, and we would venture out only by dusk, when it turned decidedly cooler. One evening, as a sweet autumnal nip stole into the air, we honked our way ‘downtown’, determined to visit one of the famed gardens of the city. As the car drove in a series of starts and stops through the knot that funnels traffic into the Dal Lake area, I wondered what other disappointments were in store for me. The Dal Lake, like the Ganga, had fallen prey in recent times to the thoughtlessness of man, and had more than once been declared to be dying. As for the gardens, I hoped they had not been ceded to the greed of builders who had started constructing high-rise apartments on the generous stretches of once-fertile land.

I need not have worried, not about this at least. The lake stretched alongside the road, looking dazzling in the setting sun, the line of shikaras with exotic names adding the picture perfect touch. The mood suddenly turned magical. When, as if on cue, the car radio burst into ‘Taareef karoon kya uski’ from the film Kashmir Ki Kali; it was serendipity indeed!

Time and again, we would evidence honesty in those who served to maintain or guard public spaces

Integrity intact

There is no parking allowed by the lakeside promenade, so we scuttled across the road when the car dropped us off in front of the Nishat Bagh gate. As we tried to enter, we were stopped and the demand for an entry ticket presented itself. We were then told the ticket window was around the corner at the end of the gate wall. Loathe to descend the steps and walk down the crowded road, we grumbled to ourselves only to have the watchman tell us we could give him the money… he would get the tickets for us. 20 rupees changed hands and we were ready to set off on our explorations. But the watchman stopped us, telling us to please wait. In five minutes, a boy came running up to hand us the tickets. Ashamed at the thought we had harboured that the watchman would pocket the ticket money, we finally set off. Time and again, we would evidence such honesty in those who served to maintain or guard public spaces.

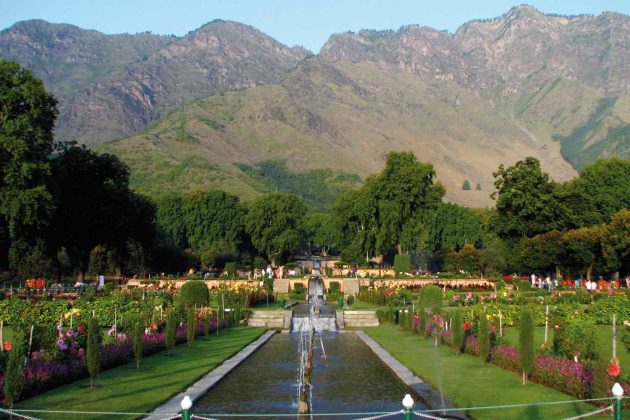

The Nishat and Shalimar Gardens of Srinagar date back to the Mughal times. And even today, despite the strife that brings the city to a frequent standstill, flowers bloom in these spaces in abundance, the fountains spray sweet water, and the old natural water-flow from one level of the garden to the next and the next, through the six levels, is maintained in quite its original glory.

Kashmiris as well as tourists find respite and pleasure in the green lawns and flower decked walkways, the magnolia blooms secretly overhead, and the chinar trees stand majestically like sentinels guarding the place. A bunch of school boys come rushing in and, stripping their uniforms, jump into the pools to gambol. It is as innocent and natural a sport as any that time has witnessed. It is impossible to imagine this in cities and towns elsewhere, except perhaps during the rains.

Development destroys

Verily, much of Srinagar is caught in a time warp. If you stop to listen, it is possible to hear the gentle cadences of poetic Urdu politeness, experience a hospitality that went out with the western concept of entertaining only invited guests on pre-ordained occasions, and feel the shaping hand of nature in the ways your days and nights are spent.

But even as I write this, my heart quails when I remember the ride back. I recall returning from the peace of the gardens, only to spy the first real mall that stands at the edge of the main road, a forerunner of the others that will perhaps soon follow. I think of the tourists who will return in summer, with loud, boisterous voices, and haggle with the shopkeepers over the price of the exquisitely embroidered garments and awe inspiring papier mache bric-a-brac, and upturn the way of life that prevails here. And I find myself wondering how the flyovers and the paved roadsides—malaises that come with prosperity and development—will change the quiet charm of this city irrevocably.

A week after I leave behind the Valley, the rains wash through it, wrecking havoc through the populated areas, laying waste to saffron fields and fruit orchards. It is as I feared. Development, I tell myself, needs to keep nature in mind and be shaped to suit each place differently. One size does not fit all! Srinagar proved it all over again, as Uttarakhand had a year ago. Why aren’t we listening?

Photo Credits

- Dal Lake Pic courtesy: Licensed under [CC BY-ND 2.0] from Colin Tsoi [flickr]

- Nishat Bagh Pic courtesy: Licensed under [CC BY 2.0] from McKay Savage [flickr]

- Florist Pic courtesy: Licensed under [CC BY-SA 2.0] from Fulvio Spada [flickr]