“Madam, look straight ahead and then a little to your right. I am the tall man in blue waving at you,” he said for the third time. I was at Kathgodam station, which is only as big as the size of the food court of New Delhi railway station, waiting with my two boys, to be taken an hour away to a colonial homestay atop a hill in Bhimtal. When I finally spotted the taxi driver I realised he had been five feet away from me, had spent 15 minutes just to make me spot him and was actually a short man in a green shirt! The unexpected nip in the air and the drizzle as we crossed the road made my antennae stand up. Have I packed enough for my three-year-old? Did my husband keep his wind cheater? Is it going to get colder?

I brushed off all worry. I had promised my husband that I would relax the feet of my mind and not fuss over whatever roles I played at home. We called our weekend trip the ‘Do Nothing Vacation’ and that was to include keeping not just sight-seeing lists unborn but also all concerns of the brain standing at ease. Little did I know then that what I had shrugged off with an easier-said-than-done expression was going to become a doable mantra for my vacations.

Much like so many towns of Uttarakhand, Bhimtal too has a lake for a heart, a temple on every hillock and ringlets of red sloping roofs surrounding them all. Typically, one would visit to go boating on the lake, eating noodles by the lakeside, posing by the hills, visiting the Gods and overall, breathing in the idea of a ‘hill station’. Not so typically, a tourist might book a homestay a little away from the hustle, carry shoes for easy trekking but also slippers for lounging around and no agenda except to eat fresh home-made food between doing something and doing nothing, alternately.

Doing something

A nursery-goer is a teen only when he reasons back. At all other times, his feet still fit in shoes not nearly the size of your hands. Which is what we kept in mind when we decided to indulge in three physically-involving activities, if only to rev up the hunger pangs for gorging on the delicious fare our hosts had to offer.

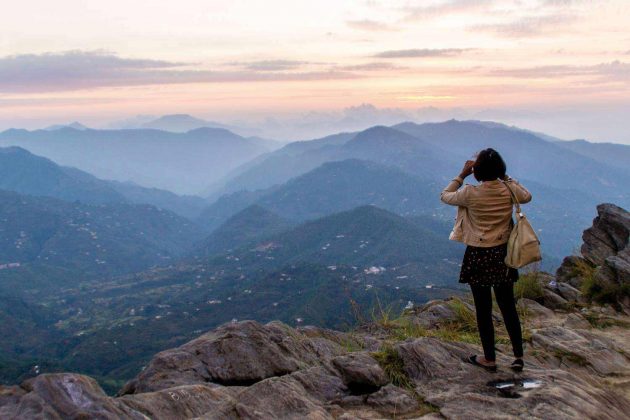

A long, circuitous drive away from our homestay lay Chauli Ki Jali, in Mukteshwar. I decided to trust the ‘Tall, blue shirt’ and make that day’s sunset special. The moody mountain weather had gone from chilly to sweaty, but oh dear, “Madam, if AC is on the car doesn’t climb”. Three city-bred spoilt brats dripped their way to what we were told was a breathtaking view from a rocky ledge. It was the absolute truth! As if the mountains were sentinels for a sun which was blushing, trying to hide behind their arms and yet eager to be admired as the clouds made way and stood by. I felt fortunate to have reached in time before it blinked for the night.

Over dinner, the cook told us about the legend associated with the place. How women would crawl through a narrow tunnel and sit perched on a precarious rock to prove their ‘morality’. As luck would have it, none in the history of Chauli ki Jali had lost their life to yet another unfavourably designed exam. Would I have survived it? I quickly filled up my mouth with a spoon full of caramel custard. The deliciousness dispelled all needless clouds of doubt.

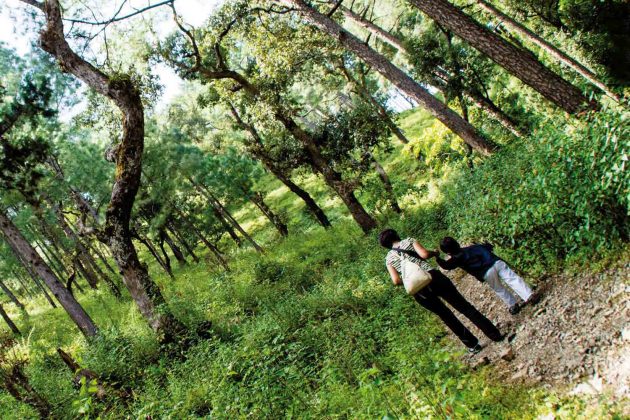

Snaking through mountain roads as a child always made me wonder what lay beyond and below the fence which marked the edge of a road. Can one see where exactly two mountains meet in a valley overgrown with wilderness? A neat line, perhaps borrowed from a map, and as illusory? I did find out when we three trotted off for a Village Walk in Nathuakhan the next morning. With every step downhill, the paths were increasingly wet and slippery—or not there at all. What was there in abundance though were all shades of green and they were getting darker with the descent. A corn plantation shared apartment space with a cow shed. A few steps below stood a temple tree—old, grand and worshipped. I remember looking up from the bottom right to where we began at the top, my line of vision crossing houses and curious children, women carrying big bundles of sticks on feet in broken rubber slippers and past cracking sounds of pine cones. The sky looked as blue but the world around me was so far removed from what I witness in Delhi, it is difficult to imagine its existence sitting at my writing desk today. Likewise, the exact mountain scent without feeling nostalgic.

On his father’s shoulders, my son climbed all the way up that day, after much convincing that for the cute calf there was not room enough. I looked at my husband’s shoes leading, feeling for steady rocks. I wasn’t worried, at all. If anything, I was glad to see how the workings of gravity were well known to this clever three-year-old.

Clocks in cities run much faster than they do in small towns. And on hills they often seem to come to a standstill

The next day, rather encouraged, we decided to trek up to the Ridge, for a picnic. The Ridge is a long and narrow flatland which is essentially the top of a hill, overlooking Sat Tal on one side and the main town of Bhimtal on the other. With sticks in hands and the enthusiasm typical of early mornings, three pairs of feet set out to climb towards the prospect of earning their paranthas and apple pie. With frequent breaks for gazing at the world below or at the size of wild mushrooms, never seen before, we were finally perched at a point where, call it my hunger talking, everything seemed bite-sized [though not the lovers sitting across from us, disappointed at the intrusion]. There is something about being a family which sharing a meal brings out. If that meal happens to be some miles above the sea level, it’s closer to divine in all ways—a sense of oneness that nothing else can make you feel. Not just with one another but also with the nature that surrounds you: the breeze that keeps you cool, the canopy that provides shelter. Is that what the lovers were thinking sitting where they had walked hand-in-hand, far away from us now, under a tall fir?

This time, the daddy had done his homework and made the boy collect daisies for his mother all the way down. On his own two feet, walking by himself, rules of gravity forgotten.

But mostly doing nothing

Clocks in cities run much faster than they do in small towns. And on hills they often seem to come to a standstill. While with much bravado I fill you up on all that we did on the spur of the moment over the three days in Bhimtal, it barely covered a fraction of the time we spent doing… well, nothing at all!

How do you do nothing? Can you? Is it possible to empty the mind of all to-dos and tasks, thoughts that bother and deadlines of lives you and me call ‘ruts’ yet run circles in? It’s possible. It’s possible to do nothing but lie inside a child’s tent, pretend camping and make up stories about the grasshopper that hopped over to get a glimpse of the boy who finished his milk. It’s possible to sit a few yards away from this action, with a book, immersed in its joys. It’s also possible to just stare into infinity, and at birds who with their fluttering, bring you back to reality. There is enough in nature to create wonder and awe and as many nooks to visit with a beau, a boy, or a book. It is times spent thus that make you feel you did nothing and yet you realise how invaluable they were because you actually filled up those hours doing what you never get enough time to. How refreshing!

This was the first family vacation where I let all today’s worries and tomorrow’s agendas take wing like grass held up in the wind. It was almost a study in contrasts, of doing and not doing. A hangover of the intoxicating ‘letting-go feeling’ was carried back to New Delhi, enough to notice the tiny nose runny as soon as we bundled up in the train that was homeward bound but saying with conviction, “You’ve climbed mountains, my son. What can a silly runny nose do to you?”

The feet of my mind were indeed relaxed.

Photo credits

- View from atop a hill in Bhimtal and Trekking with my little one up to the Ridge: Sakshi Nanda

- There is enough in nature to create wonder and awe: Licensed under [CC BY 2.0] from Sanjoy Ghosh [Flickr]

This was first published in the April 2015 issue of Complete Wellbeing.