I am following in the footsteps of Elizabeth Rohm. The actress who plays the role of a District Attorney in the TV series Law and Order, played Juliet Palmer, the skeptical journalist in the film Finding Happiness, as she went about exploring the many layers of Ananda Village, in California.I am not quite as skeptical, but being a journalist nonetheless, I keep my antenna up and my eyes open.Ananda Village is an approximately 900 acre area in the pine dotted foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Undulating greens and wooded slopes make the surroundings scenic. The Village was set up 40 years ago by Swami Kriyananda, disciple and inheritor of the mantle of Swami Parmahansa Yogananda, whose Autobiography of a Yogi still attracts people to the Guru’s philosophy and way of life.

Ananda Village was to serve as a retreat for those who sought a new and inclusive way to the Universal Spirit of God, away from the race tracks that those who ran the rat race for success and money frequented. It was an experiment about a new way of life.

The new way of life presents itself to me right the first morning. Breakfast is an offering of completely organic food, eaten in a silence that is in some ways meditative. Beyond the dining area, kriya yoga practitioners, who work to keep their training course fees low, rustle up hot food and wash the mountain of dishes, which appears after each of the three meals. What is strangely pleasant is that none of them seem to find the chores tiresome; but go through them with a dash of cheer.

The Ananda philosophy speaks of setting aside the ego, and the regional, social and religious differences it can create, to tune in to the Higher Consciousness. Working to help one another, to do at least one service for someone else in the course of each day, and to believe people are worth more than things is a way of life here, and the results of this experiment shine through in the smiles of almost everyone I meet.

Though hidden in the sweeping foothills [largely abandoned once the Gold Rush ended], Ananda Village is a quiet magnet towards which people of all faiths gravitate. Each has a reason unique yet similar for coming here. I meet David Eby, who conducts the choir and plays the cello. He also teaches music and how it can awaken the consciousness, at the Ananda College in Portland. Soft spoken and sensitive, David tells me he has found in Ananda the end of his search for spirituality. Eby’s father was a Presbytarian Minister. “He was always busy with meetings, and I thought this was how one could be a true Christian, and followed his example,” Eby says. “One day, I was really burnt out and sick, waiting for my wife to come and tend to me. But she gave me a critical look and said, ‘if you are sick in the middle of the night, something is wrong.’ That did it. Eby did a double think. A book on meditation that he discovered in a Barnes and Noble bookshop gave him ‘a sense of peace’ as he turned the pages. Eby soon moved to Portland and joined the Ananda community there.

Others have their own stories. Virani, commonly referred to as the goat woman, found in Ananda a strength she never did quite feel in her job as deputy sheriff. “I think I was always afraid I would not live up to my role,” she confessed. Finding herself retired with a pension that let her follow her mind, Virani, who had been attending the Ananda Church of Self Realisation for almost two decades even during her years as deputy sheriff, exchanged the wide open spaces for the courtrooms and moved with her husband to Ananda. “I have a 365-day job, with each day spanning 17 working hours,” she says. Her enterprise that sees her tending her ‘goat children’, milking, playing mid wife and diary farmer as required, is a vital part of the Ananda community. But more precious than the goat’s milk she sells, is the infectious air of wellbeing and simple joy of living that she carries with her. One with Nature, she is mother to her animals, which include two donkeys with furry, receptive ears tuned in to everything she says. Their job, she tells me, is to keep the predatory mountain lions at bay, should one decide he wants a goat snack.

At the opposite end of the age spectrum is Arthur, a 24-year-old Taiwanese, who is excited over his spiritual name, Prasad, “as it signifies receiving a spiritual blessing”. Just two weeks old in the community, Prasad sits comfortably cross-legged in his office chair in the IT and web department at the Ananda Sangha office, from where he reaches out to community members and those seeking a spiritual link anywhere in the world. Dressed in yellow, like Surya, a 64-year-old colleague, Prasad is a Brahmachari [a celibate]. “We can renounce this state when we so choose,” Surya explains, “but it seldom happens.”

Colour plays a significant role in sending out messages about the spiritual states of the Ananda community members. Like Santoshi [Nancy] Kendal, my guide and constant touchboard through the week, many others wear blue to indicate they are Naya Swamis, which signifies their celibate status. If married, such Naya Swamis will sleep in separate bedrooms, but benefit from the companionship and shared sense of purpose and spiritual realisations.

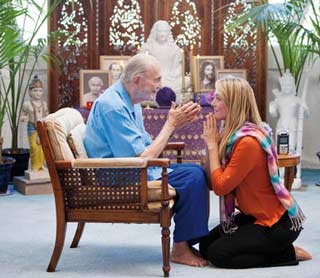

Jyotish and Devi Novak, whom I meet for an interview, are Naya Swamis and the spiritual inheritors of Swami Kriyananda’s legacy. Jyotish, who worked as an assistant to the Swami as a part of his search for purpose in life, moved at his request to Ananda. “Swami wanted to start a retreat for himself and also to teach others,” Jyotish explains. “People started coming, he had a reputation as a spiritual being, and the time too was ripe with people seeking alternative ways of life. The community grew from 15 to 40 in just three months, and soon more land had to be acquired. Ananda Village came into being,” he adds. Devi, on the other hand, feels her entire life was a preparation for where she is now. “In school I read world literature, the Gita, and when I met a teacher member of Vedanta from the Ramakrishna Society, it resonated with me, though his accent was too thick for me to understand his words.” In college, Devi continued her search reading Social Antropology and discovering to her surprise, when she read the Mahabharata, that the Gita was a part of the same epic. An article on Swami Yogananda intrigued her enough to read his autobiography, and she was soon throwing up the admission to graduate school to move to Ananda Village. “I came here on July 4th 1964, the same day the property was signed for by the community,” she says. There was no water, no power, no electric supply, but it was a ‘treasure period’ and when the Swami arranged a match for her with his assistant, Jyotish, it was as if the journey had finally reached its destination.

Jyotish and Devi Novak, whom I meet for an interview, are Naya Swamis and the spiritual inheritors of Swami Kriyananda’s legacy. Jyotish, who worked as an assistant to the Swami as a part of his search for purpose in life, moved at his request to Ananda. “Swami wanted to start a retreat for himself and also to teach others,” Jyotish explains. “People started coming, he had a reputation as a spiritual being, and the time too was ripe with people seeking alternative ways of life. The community grew from 15 to 40 in just three months, and soon more land had to be acquired. Ananda Village came into being,” he adds. Devi, on the other hand, feels her entire life was a preparation for where she is now. “In school I read world literature, the Gita, and when I met a teacher member of Vedanta from the Ramakrishna Society, it resonated with me, though his accent was too thick for me to understand his words.” In college, Devi continued her search reading Social Antropology and discovering to her surprise, when she read the Mahabharata, that the Gita was a part of the same epic. An article on Swami Yogananda intrigued her enough to read his autobiography, and she was soon throwing up the admission to graduate school to move to Ananda Village. “I came here on July 4th 1964, the same day the property was signed for by the community,” she says. There was no water, no power, no electric supply, but it was a ‘treasure period’ and when the Swami arranged a match for her with his assistant, Jyotish, it was as if the journey had finally reached its destination.

Devi admits that there was initial suspicion and resistance to the community and the experiment. “Parents would be concerned their children were being drawn into a cult, but the community drew to it hard-working, intelligent people and thus soon gathered strength. Even government organisations were hostile, till we made it clear we were not interested in taking, but in giving,” she explains, adding that when the devastating, now historic forest fire swept through the region destroying homes, Ananda Village was the only community that did not seek or accept government compensation. As spiritual leaders of the Ananda community worldwide, the Novaks travel extensively, and are hands on in developing and maintaining the tenets on which the community was intitially founded. The Pune Village, founded because the Swami wanted to “take Ananda home”, is one of the most important projects on hand.

The community can be replicated in other ways too by others, the Novaks believe. Education, farming, ecological concerns are common to all communities, and each can find its own path through sustainabilty and caring, towards spiritual growth.

It was Swami Kriyananda too, who thought of broadcasting the Village and all it stood for, by means of a movie. “It started off as a documentary, and it was only after we had shot reams of film, that we decided that building in a story would work so much better, and changed tracks,” Ted Nicolaou, the film’s director says in a Skype interview. Nicolaou has hair that suggests he has recently had an encounter with a live electrical socket, but his eyes and smile are kind and radiate a warmth that is unexpected in someone who earned his laurels making Vampire movies before moving on to his current job with Walt Disney Productions. Initially titled Cities of Light, the film was rechristened Finding Happiness, and will release in India across 12 cities between April 25th and May 1st 2014.

Ted came to filming Finding Happiness by chance. Roberto Bessi, one of the producers of the film, had also produced the Vampire movies, and knew that Ted had moved on to making biographies. “He met the Swami and thought of me for the project,” says Ted. Many meetings with the Swami followed and finally the shoot was given the go ahead. 24 days of shooting later, which included a day’s filming from a helicopter, scrapping the script he had worked out and “infinite patience to let the villagers be themselves and let Elizabeth draw them out to tell their stories”, the film was ready for post production. “I was walking on a precipice,” Ted adds, “I did not want the film to be a promo just because it was funded by Ananda, but an informative entertainer.”

The Villagers are gung ho about the film. Walking around the extensive property, it is easy to see why. Whether it is the school or the administrative offices, the farms or the IT department, everywhere I turn, there is a face that I feel is intriguingly familiar. Then I realise I have indeed seen them all before, in the movie, mostly playing themselves.

The inhabitants of Ananda Village play many parts in daily life too. It is not unusual to see a cashier at the Master’s Market store that mainly stocks organically grown produce and intriguingly named snacks like Bliss Balls and Karmic Croutons double up literally as a yoga teacher in the mornings and afternoons. Musical David Eby, who plays Elizabeth Rohm’s guide in the film, when called upon without warning to create the musical score for the film, hesitated briefly. “I said, I would meditate, and told God, “If this is what you want me to do…” And then I felt a huge Presence. And I agreed to do it.

The inhabitants of Ananda Village play many parts in daily life too. It is not unusual to see a cashier at the Master’s Market store that mainly stocks organically grown produce and intriguingly named snacks like Bliss Balls and Karmic Croutons double up literally as a yoga teacher in the mornings and afternoons. Musical David Eby, who plays Elizabeth Rohm’s guide in the film, when called upon without warning to create the musical score for the film, hesitated briefly. “I said, I would meditate, and told God, “If this is what you want me to do…” And then I felt a huge Presence. And I agreed to do it.

Miracles like these seem commonplace, but are actually just a matter of putting the mind to work for a spiritual end. Or so I am beginning to believe. How else do I explain the collection of period garments crammed into a tiny Costume Store, the owner of which takes it on herself to fit out anyone who needs a ‘look’, including a 40-member school play, sourcing from the garments she has picked up mostly from the thrift shops. Or the fascinating array of jewellery and animals carved out of semi-precious stones that Elisabeth and her husband create at the Village and take out to exhibitions in the Bay area. Then take the case of Netri who, with no training at all, on Swami’s request, designed the garden at the Crystal Heritage, that has the most intricately perfect arrangement of plants and flowers that bestows instant serenity. The garden attracts thousands of visitors during the Tulip Festival in April, who come to see the flowers in full bloom or photograph the cherry blossom that forms the leit motif of the publicity material for the Finding Happiness film.

In one of the high school classrooms, I watch a Math lesson in progress. The ubiquitous calculator is missing, the brain’s powers are being put to use as the teacher throws four digit numbers in a continuous stream and asking for totals after addition or multiplication. Hands go up, almost before he can complete his last number, swiftest among them young Som and his twin brother who are, not surprisingly Indian by birth. “Oral Math is something we all enjoy,” one of the students says. I respond that it is indeed a dying skill, and wish secretly that my Math teacher had been able to infuse my lesson with the same excitement.

By the time I leave, the Village has touched me with its aura. Our villages were once like this, I muse, as Santoshi drives me to the airport, all the way to San Francisco. In Indian communities too, everyone cared about Nature and nurtured one another; tasks, sorrows and happiness were shared too. Where had all of it gone? Would we have to learn it all again, like we did yoga and meditation, imported back to us from the West?

Perhaps! If so, Swami Kriyananda’s mission would be accomplished!

This was first published in the April 2014 issue of Complete Wellbeing.

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!