I was passing through the Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary in Bandipur, Karnataka. A lone pachyderm stood by the road, swaying his tusk and grazing the grass. I stopped the car and gazed at him. I remembered someone telling me an elephant who roamed all alone was considered dangerous. I wondered if this one would go rampant but soon spotted his fellow herd-mates behind the tall bushes. They looked majestic and intimidating as a group.

Although I could have stood there and admired them all day, I had to bid adieu to these beasts; I was on my way to the land of tea, coffee, rubber and spices—Wayanad, Kerala.

Ancient caves and misty waterfalls awaited me

Wayanad lies perched on the fertile hills of the Western Ghats, covered in dense foliage. As I drove into the district, the road snaked and curved through the verdant hills that are peppered with ponds and lakes.

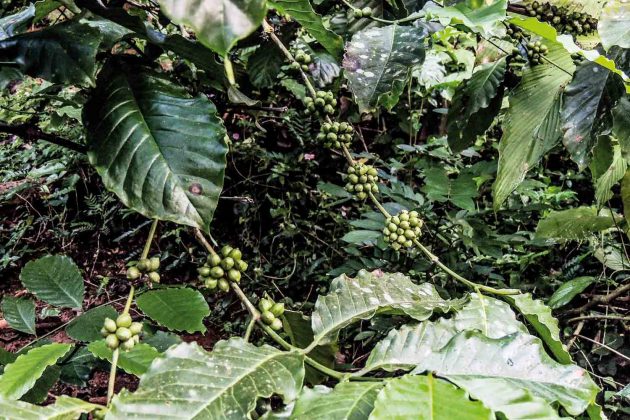

My first destination was the Edakkal caves. Located in a remote area in the district, these caves lay surrounded by sprawling coffee plantations. To get there, I had to make my way through the town of Sulthan Bathery, its name a corrupted form of Sultan’s Battery. The great ruler Tipu Sultan had stored his ammunition and artillery in an old Jain temple here. The beautiful temple still stands strong after all these years.

The security personnel tagged the plastic items I had in my bag to make sure I brought them with me on my return

Onward I went, making my way to the Ambukuthimala Mountain, atop which lie the caves. It’s a 4000-foot hike and I managed to trudge my way to the top. Climbing around 300 steep steps for an hour left me huffing and puffing in the warm weather. At the entrance to the caves, I was surprised and glad that the security personnel tagged the plastic items I had in my bag to make sure I brought them with me on my return.

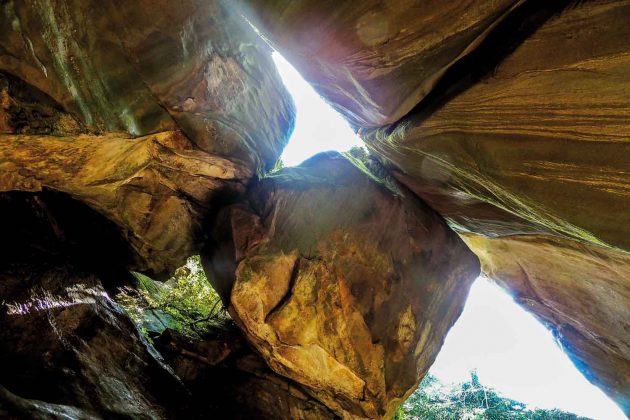

The name “Edakkal” means “a stone in between” and is a reference to the giant boulder that apparently wedged itself between two huge rocks to form these pseudo caves. Although they were discovered by a British officer in 1895, these caves are home to etchings and pictorial writings that are around 7000 years old. As I looked at these pictures of pre-historic humans, animals and customs, I couldn’t help but ponder over how life must have been like in those times.

After the caves, I next wanted to explore the Soojipara or Soochipara waterfall. I drove to the village of Meppady and then made my way to the waterfall. The scenic cascade’s name means “needle-like [sooji] rock [para]” and refers to the thin, spiky rocks that lie at its base. To get to the waterfall, I had to trek downhill on a stony path; then finally I saw the torrent pouring like a dream, with its mist spraying in all directions. I was drenched and refreshed basking in the fresh mountain air and water. My first day at Wayanad had tired me but it had also tickled the explorer in me.

There were fresh green tea gardens on hilly slopes and long pepper vines were draped around the majestic silver oaks

Spice central

A search for a place to put my feet up took me to the picturesque village of Vythiri. I could hear the azaan, the Islamic call to worship, being played in the nearby mosque. As I took in the beauty of the village, I noticed that the landscape had changed. There were fresh green tea gardens on hilly slopes and long pepper vines were draped around the majestic silver oaks. Every tea plantation was an abode of spices.

As I entered the grounds of Pranavam homestay, I noticed the grass growing under my feet was actually a wild variant of coriander and it had the same strong fragrance. My eyes scanned the yard and found turmeric and ginger shrubs crowded together by the fence and green chillies hung on tender twigs. A walk around the village, after resting for a bit, was a treat for my senses. Cloves, bay leaves and cardamom were found in copious numbers throughout the village.

Among the many natural beauties I saw were several kinds of birds, like hornbills, bulbuls and kingfisher

The next morning I woke up early so that I could take in the dew-laden sights of the area. Walking through the paddy fields and betel nut groves, inhaling the fresh morning air, to view the first daylight are experiences that shouldn’t be missed when in Wayanad. Among the many natural beauties I saw were several kinds of birds, like hornbills, bulbuls and kingfishers.

Back at the homestay, a scrumptious breakfast was prepared for me. I dug into the spread of hot idiyappams, boiled nenthra pazham or banana halwa and finished it off with steamed rice cylinders called puttu. The authentic Kerala breakfast packed me with energy for the adventures that awaited me.

Tribes of Wayanad

It is estimated that 17 different tribes inhabit the region of Wayanad, with Kuruchiya considered the highest caste. My first stop was in the village of Thrikkaipetta where I discovered an NGO called URAVU, which helps the local tribal community by providing them with sustainable work. They teach the locals how to make various environment-friendly products from bamboo—bags, furniture, handicrafts, utensils and curtains. This has not only helped the tribal people find a stable livelihood, but it has also encouraged sustainable practices.

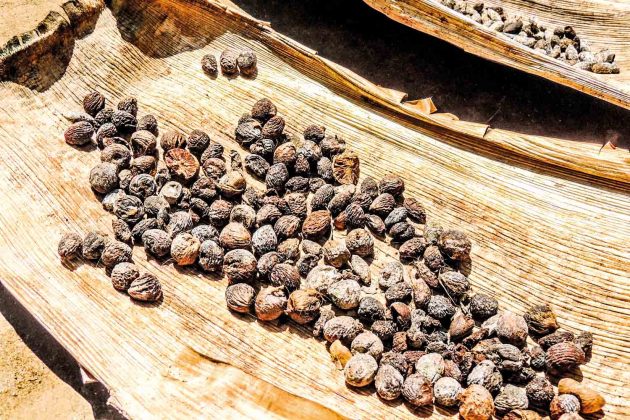

Next, I moved on to the village of Ambalavayal. One of the sights that first caught my eye was the betel nuts that were laid out to dry in the various courtyards. I was there to visit the house of a Paniya tribesman, Vellan Moopan. As I stepped into his home, I could hear the low pitch of a musical instrument. Upon moving in further, I saw him scrapping the thudi, a local percussion instrument. Made of sheep skin, jackfruit wood, bamboo and latex, the thudi is played at the tribe’s funerals and marriages. It normally takes 20 days to make one thudi. Sadly, Vellan is one of the few artisans left in Wayanad who are working hard to save this traditional art form.

The people of Wayanad haven’t forgotten their roots even though the bustle of modern life surrounds them

For lunch, I had brown rice with fish fry and curry, with a side of boiled tapioca and red chillies chutney. Fish is found in abundance in Wayanad and is part of almost every meal.

It was time for me to move ahead and visit Govindan from the Kuruma tribe. One look at his belongings, which were bows and arrows of various shapes and sizes, was enough to tell me that archery was in his blood. A keen instructor, he tried to teach me the ancient art. After many failed attempts I gave up and was content to sit and eat the canistel that he offered me. Canistel is also called eggfruit because of its flesh, which tastes just like a boiled egg’s yolk.

A model for the rest of us

In those few days in Wayanad I noticed the people of this land had learnt to live in harmony with nature. By adopting sustainable practices and preserving traditional art forms, the inhabitants had learnt to live a simple yet contented life. They haven’t forgotten their roots even though the bustle of modern life surrounds them. I was puzzled as to what motivated them to live like this. A native gave me the answer: “These are our jewels and we better protect them before they are lost”.

This was first published in the September 2015 issue of Complete Wellbeing.