I have always been interested in textures, colours and creating things with my hands. The natural landscape and architecture that changes, either by natural forces or through human hands captivates my imagination. So working with clay seemed most natural to me, especially since it combines all elements: earth, water, air, fire and ether.

My journey with clay

Having been a furnishings consultant for 13 years and then a yoga teacher for three years, I finally allowed myself in 2009 to begin learning pottery with studio potter Vinod Dubey in Mumbai. The feel of clay on my fingertips brought me into the here and now. Its strength and flexibility released something within me and I found myself breathing so easily and in such a relaxed way that I just wanted to spend all my time mucking around in clay.

This inspired me to pack my bags and shift base to Pondicherry to learn this intriguing art from Ray Meeker and Deborah Smith, an American couple who have been running Golden Bridge Pottery for 40 years. The pottery studio admits only four students each year. After a two-year waiting period, tons of persistence and a stroke of good luck, [the fourth student who had enrolled dropped out] I was offered the space.

I was a complete novice potter [I called a kiln an ‘oven’] but the ceramic process showed me how my ideologies could be translated to practical living. My monkey mind finally found a place to rest. I could settle down with the lump of clay in my hand, pushing, pinching and just being with it. This communicating with clay taught me the language of my own mind. All that I had learnt, read and conceptually understood in yoga finally began to seem more meaningful and profound. Clay has become my teacher, my guide and my sweet but extracting companion.

The process

Wedging: All the clay is prepared by hand, right from pounding the different clays to sieving, slaking and drying. This is the starting point, where you prepare or mix the clay. It’s similar to the asana practice in yoga because scattered energy around the clay is harnessed and gathered within it. The potter energises the clay and it is now ready to be used.

Centering: When centering the clay to the wheel, I had to stop thinking of everything else and just be in the here and now with the lump of clay in my hands. Also, learning on a kick-wheel made it tiring initially as I had to keep kicking to rotate the wheel. Centering was a challenge that took me four months to learn. Learning to centre the clay can be frustrating, as the clay does exactly what it wants. It would make my hands dance all over the wheel. At times, I would feel it was laughing at me. If I would try to use my physical strength to make it obey, it would submit, but so unwillingly that it would look lifeless. I realised I had to work in partnership with it and harmonise myself to it. I had to find out its nature, what it can do, what it will allow and what it will resist. Sounds like getting to know another person? Well, it is just that—a complete person with personality traits and attitude too. Each clay type is different. Some clays allow you to stretch it a lot. Others resist any attempt to shape them. The secret is in getting to know your clay. Then you can make it work with you.

Creating cylinders: When I lifted the centered clay to make a cylinder, it was me and the clay working together. I would describe that feeling like the satisfaction you get when you eat a nourishing meal, much like a deeper level of contentment.

When you finally create a form and hold it in your hands, nothing can match that feeling of awe and wonder. It’s addictive. And worth every bit of mucking around, back-breaking clay wedging, tears of desperation when learning and failing, and hours bent over the wheel.

Learning to pot [or anything else for that matter] is a question of abhyasa and vairagya [discipline and trust]. You have to have faith in the process, trusting that the practice will get you there sooner or later. Failures and facing the unknown are the steps that I had to climb to reach my goal. This was an act of trust in myself and in the scheme of things.

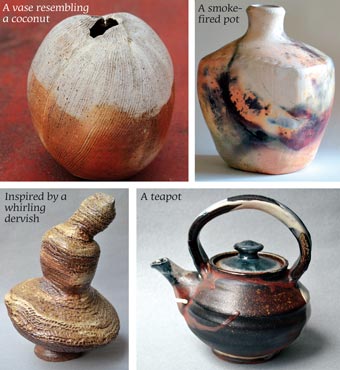

Firing, the amalgamation stage: My dried pot was now ready to meet fire and air and turn into something rigid, hard, and permanent [somewhat!]. As I fed the wood, it crackled and released its energy to the pots. The sound was a howl and the colours within the kiln pretty much covered the entire spectrum: blues and greens, oranges and reds, even pure white. Before technology gave us the pyrometer to read temperature, potters would know the temperature in the kiln by just looking at the colour of the flame.

Firings are a continuous cycle of feeding wood and checking the kiln interiors and the cones. It’s a long learning curve where so many factors affect the final results. Just the way you place your pots inside the kiln can affect the outcome. This is the point where you just have to accept and surrender to the way things are going and do the needful without knowing the outcome. Vairagya and karma yoga, thinks the yogi, smiling.

Cooling the kiln: After the exhausting firing stage, comes the time for cooling of the kiln. Here you try to recuperate, but without worrying about the results. Opening the kiln is the most exciting, crazy and exhilarating part. Each pot will tell its story, where the flame licked it, where the ash settled on and which part didn’t get enough energy. As every high is followed by a low, so sitting with your kiln load of pots is a time to introspect. All the mistakes are visible, some known… a lot unknown. How much you loved and enjoyed each stage of the process shows up. A well made pot thoughtlessly glazed, a well-glazed pot carelessly handled or a cherished pot turned alive by the flame.

Finding an owner: My job is incomplete if I don’t take the pot to a right user. It is alive and ready to start conversing with its owner. And I too will be a part of this conversation. The story of its creation is meaningless if there isn’t someone to listen to it. This sharing is what delights me, reinforces my faith in our interconnectedness. It makes me want to create something of use, of value, of beauty so that I can share my delight. So I continue playing in the dirt, digging deeper into myself, exploring unknown terrains and finding more connections to myself and through my pots to everyone else.

And the beauty is that even on making the 100th pot, the amazement and joy never dwindles.

At times I was overwhelmed with doubts: How am I going to decide on a form? I love it but how come everyone else thinks nothing of it? How do I be ‘original’? How am I ever going to sell my work? Will people respond to it? The list went on. But, in spite of such thoughts, I felt each day was meaningful and I was doing something worthwhile, even if the only thing I would have done was pounded 20 kilos of clay and not made a single satisfactory pot that day. But I knew I was pursuing what is closest to my heart, and that meant a better chance of leading an authentic life.

I’ve been told that it takes seven years of practice to become a proficient potter. Well, I shall know if it’s true in time.

Created from clay… will return to clay

Created from clay… will return to clay

I had laboriously made a few pots over a week and very proudly kept them to dry out before firing. That night it rained and the next morning I found lumps of clay where my pots had been. I went to my teacher in search of sympathy and the response I got set me right, “So what? Make some more pots.”

This was first published in the December 2013 issue of Complete Wellbeing.

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!