If negativity were an Olympic event, I would be from a family of gold medalists. I grew up with an ever present sense that no matter how successful I might be now, the next step was bound to be my doom. In elementary school, I was a straight-A student, but I would stay awake nights before a big test, literally becoming physically ill, because I was certain I was going to fail. My fear was not that I would make a B or even a C. And I didn’t think of it as a fear. I experienced it as a certainty: tomorrow the bottom would finally drop out, and I would fail.

How much more relaxed would I be, how much more my true self, how much more productive and efficient and effective, how much more loving and generous and focused would I be…if this fear didn’t live in my chest?

I have a friend who seems fearless in the face of decision, even big, ominous, important decisions. He doesn’t say he’s fearless, only that he is “not particularly influenced” by fear. I am not like that, and neither are most of the people I have spoken with through the years. Fortunately, those of us who are afraid and who are “frequently influenced” by our fear are the norm. We are not alone. That is always good news.

We all know fear. Fear is our constant companion, our day-to-day nemesis, and our ultimate challenge. Fear fuels our negative and judgemental thoughts and our need to control things. Fear underlies guilt and shame and anger. Every difficult emotion we experience represents some kind of threat—a threat to our self-esteem or to the stability of a relationship [personal or professional], even to our right to be alive. And threat translates to fear. Start with any difficult emotion you choose, get on the elevator, press B for basement, and there, below the guilt and shame and anger, below the negativity and the judgements, you will find it: fear.

Fear takes many forms: dread, worry, panic, anxiety, self-consciousness, superstition, negativity. We can worry that our shoes don’t match an outfit or worry about larger concerns like world hunger. We can be somewhat nervous about performing at a recital or seriously nervous about the results of an HIV test. And it shows itself in many ways: avoidance, procrastination, judgment, control, agitation, perfectionism. These are just some of the guises of fear.

It’s what we all have in common. We will experience fear in different ways, depending on more variables than we could possibly count, and we will respond to fear in our own ways. There is no escaping the fact that fear is a universal experience that we share not just with other human beings, but with all creatures. Sometimes I think the primary difference between how my dog and I experience fear is that he tends to be afraid when there is legitimate danger, while I have the capacity—and the inclination—to scare myself with my highly evolved mind in the absence of any real threat. Or we can take any legitimate fear and work with it until we are paralyzed, barely able to get a decent breath.

My work as a psychotherapist has been largely about how to claim our right to live without fear of internal war and destruction. I have spent thousands of hours in conversation with people—individually and in groups—working to increase understanding and solve problems. I couldn’t possibly recall all of the various strategies, techniques, and philosophies I have enlisted toward these ends, but I can report that no matter what the approach, in every single difficulty I have encountered—mine or someone else’s—fear has been involved.

Sometimes fear is part of the problem. Sometimes fear is the problem. And when we are really paying attention, fear is usually part of the solution. Fear is an essential part of our nature, installed in our DNA, no doubt for very good reason.

Bully and Ally

Although fear is a major influence in every one of our lives, it is not always negative. It is essentially a positive mechanism, an ingenious natural design to keep us safe. And there are plenty of opportunities for that healthy fear to work its magic, guiding us this way and that, alerting us to danger and aligning us with what is good and right in the world.

Fear is an alarm system. It is there to get our attention, to push us in one direction or another, out of harm’s way. We must emphasize this from the very beginning: our natural mechanism of fear is not the problem. We have used our higher intelligence to create a monster out of what is essentially a healthy, natural response to adverse or potentially dangerous situations.

It is essential that we begin by differentiating between healthy and unhealthy fear. The anxieties and worries that pervade our daily lives—the real troublemakers—are not born from healthy fear, but from neurotic fear. Healthy fear stands guard responsibly, informing us immediately of real danger. Neurotic fear works around the clock, exaggerating and even inventing potential dangers. Healthy fear is about protection and guidance. Neurotic fear is about the need to be in control. Healthy fear inspires us to do what can be done in the present. Neurotic fear speaks to us endlessly about everything that could possibly go wrong tomorrow, or the next day, or next year. I encourage you to personify each of these, creating specific human images to characterize your healthy fear and your neurotic fear. See them as two advisors, each with his own personality and agenda.

Most people will recognize these two advisors. Some of us may say we know them intimately—especially the neurotic fear, the one my wife calls the “Bully” and one of my clients calls the “Chairman.” He will never be caught wearing a “Bully” name tag. More likely he shows up claiming to be “the voice of reason,” “the realistic one,” “your best friend,” and sometimes “your only hope.” Healthy fear, the one my wife calls the “Ally,” is not pushy. This one is clear, direct, and to the point. The Ally lives within us for one reason only: to protect. The Bully, on the other hand, will claim to protect, and may even intend to protect, but will continually step beyond the bounds of that job description. The Bully overprotects, to the point of control.

We lean toward the voice of neurotic fear. And we continue to do so even after we have uncovered the more authentic voice of healthy fear. Faced with this choice, how could we possibly continue to take the obviously negative option? Are we that inherently negative? Do we like being afraid all the time? Are we just stupid?

The answer is none of the above. We are not inherently negative, we don’t enjoy scaring the hell out of ourselves, and we are not just stupid. Neurotic fear has firmly established itself within our consciousness in two major ways.

First, and most simply, the neurotic-fear messages have embedded themselves into our thinking through the years of sheer repetition. And, second, as a natural result of such repetition, the messages have achieved a high level of credibility.

They are so familiar that we tend to trust them. In other words, we have been steadily and thoroughly brainwashed by the Bully. Isn’t it time you fired the Bully who has been running your life? Isn’t it time to put yourself in charge?

Taking charge

The challenge we face is to reverse that brainwashing, to learn to do more than lean away from the voice of neurotic fear. We must learn to make the conscious choice to turn away from the Bully and toward the Ally. It is still not easy, but with repeated practice and focused attention, the voice of the Ally, with its strength, credibility, and wisdom, begins to assume its rightful place in our consciousness.

Fear is not the problem. It is our relationship to the fear that determines the choices we make. By changing our relationship to fear, we reduce its credibility, robbing it of its power to stop us. It’s sort of like demoting your fear, busting it down to a lower rank.

Four steps to transforming your relationship with fear

- Face it.

- Explore it.

- Accept it.

- Respond to it.

Facing our fears

An invitation to speak at my undergraduate alma mater catapulted me twenty-five years back in time. Arriving the night before I was scheduled to give a lecture, I decided to take an evening walk across the college campus where I had spent four of the most important years of my life. With the exception of two or three new buildings, everything seemed basically the same as when I left. What alarmed me was the inescapable feeling that I was basically the same too. I realized I was the same person who had graduated twenty-five years before in one very specific—and not very flattering—way: I was still scared.

As I walked the campus that night, I could not shake the feeling that I had not changed all that much. It didn’t make much sense to me, but I could almost hear a little voice within me saying, “Thom, you are still scared.” The little voice—whoever, whatever it was—was not talking about me being a little nervous about the speech I was there to deliver. It was talking about fear being a central, possibly even organizing, element of my very identity. “Fear still has too much power in your life,” it said. I knew my life had been more than just fear. I did not forget the obstacles I had overcome or the courage that had guided me into and through some of the darkest places in my consciousness. I had been in recovery from alcoholism for a dozen years and been successfully treated for depression for six years. I had a well-established therapy practice in which I guided many others through difficult times, important discoveries, and life-changing decisions. I had written and published several books, accomplishing a lifelong dream. But the fear was always there. My first marriage had not survived, but now I was happily married, living in a real-life, healthy, adult relationship. But the fear was always there. It had always been there.

In spite of all I had accomplished and all I was grateful for, I realized in that moment not only that fear had always been there, but also that much of the time fear was still in charge.

As I walked from one end of that campus and back, I was in class once again. Forget about the lecture I was there to give; here is the lecture I was apparently there to get. Even though I cannot explain exactly how it works, these are the words I heard, or felt, or both:

“Pay close attention. Listen carefully. Let’s look at what happens when fear is in charge. With fear in charge, you can never fully relax, let your guard down, be your true self. You can’t open up because you are afraid of how people will respond if they were to meet the real you. When fear is in charge, you simply cannot take that chance. Fear will not allow honesty, fear despises spontaneity, and fear refuses to believe in you. Fear may mean well, but it ruins everything by overprotecting you, insisting that you stay hidden and keep a low profile, promising that your time is coming…sometime later. Fear is bold, but insists that you be timid. Take a chance and there will be hell to pay: fear will call on its dear friend, shame, to meet you on the other side of your risk taking, to tell you what you should not have done. Fear will trip you, tackle you, smother you, do whatever it takes to cause you to hesitate, to stop you. In this way fear is fearless. Fear will remain in charge for as long as you let it. It will never volunteer to step down, to relinquish its authority.

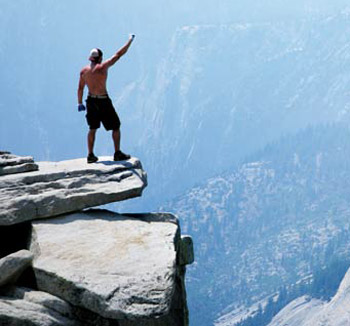

“Your assignment is to live a life that is not ruled by fear. To do this, you must be able to identify, at any given time, exactly what fear is telling you—or rather threatening you with—and to disobey its instructions. Every morning when you awake, make a conscious decision to remain in charge of your own life. Fear cannot occupy the space in which you stand. Fear cannot force you out of that position of authority, but it can, if you let it, scare you away. “Let your personal motto be ‘NO FEAR.’ Say those two powerful words as you put your feet on the floor, as you look into the mirror, as you walk out the door. Ask yourself each morning, and all through the day, what will NO FEAR mean for me today? “Ask yourself the question…and don’t forget to listen for the answer.”

I wrote that lecture down when I returned to my hotel room and thought about the answer to that question. What does the NO FEAR motto mean to me? I realized that NO FEAR means that I will not let fear determine my every move. It means that I will look the Bully straight in the eye and say, “No, you cannot control my life. I am in charge here.” And I realized that NO FEAR does not mean that there will be “no fear,” but that I am committing to saying NO to fear. I have done my best, as the imperfect human that I am, to carry the NO FEAR motto with me every day. It has helped me take important new steps in both the personal and professional aspects of my life, but it has also given me new lenses through which to view our human condition.

I encourage you to adopt the NO FEAR motto as your own. Find ways to bring it to mind throughout the day. One of my clients, Lynn, keeps the words “NO FEAR” taped to her bathroom mirror, and the initials, “N.F.” on her refrigerator and on the steering wheel of her car.

The more you rehearse the NO FEAR motto, the more natural it will become. Don’t think that the motto will replace or take away fear, because it won’t. Just install the NO FEAR motto right next to your fear. Remember that the little voice told me that “the assignment is to live a life that is not ruled by fear.” It didn’t say anything about being without fear.

Repeat the motto to yourself frequently throughout the day. Make it your mantra. Whether this feels like a powerful spiritual practice or simply something to mutter under your breath, make it a habit. Before you begin something that feels stressful to you—giving a speech, talking to the boss, standing up to a friend or family member—close your eyes for just one moment, take a few deep breaths, and repeat the motto slowly with each breath.

When you adopt the NO FEAR motto, you are making a commitment to the first letter of our acronym map: facing fear. When we begin with the first step in our acronym map, facing the fear, we put into play what I have come to think of as one of the most underestimated and underappreciated agents of change: awareness. Simply put: darkness is the absence of light; where light shines, there is no darkness; and awareness is that light.

A significant part of what I do for a living is accompany people into their psyches with my trusty flashlight. [I once heard someone say, “My mind is like a bad neighborhood—you don’t want to go in there alone.”] We shine the beam of light here and there, destroying darkness. The interesting thing about the light of awareness is that once it has revealed something to us, even when the light has gone and the darkness returns, we still know it’s there. Once something has been revealed to our conscious minds, we can never return it to the anonymity of total darkness—because we know it’s there.

And so it is with fear.

Simple and powerful awareness is the first step to take.

Ironically, the only way to activate the NO FEAR motto in your life is to move directly toward the fear. Be aware of your fear. Don’t run. Don’t hide. Don’t cover it up with excuses, apologies, self-judgement, or mood-altering chemicals. Move straight toward it. The fear you have spent a lifetime trying to ignore is about to become one of your greatest teachers.

Don’t expect to fully comprehend this all at once anymore than you would expect to simply exorcise all fear from your life. It is progress we seek, not perfection.

Exploring our fears

Over the past twenty years, I have accompanied men and women as they faced fears of all sizes—small, medium, and large. The life circumstances associated with the fears come in many forms as well, from the young man who came to see me to bolster his confidence after receiving a significant promotion at work, to clients who have endured terrible abuse as children, to those who face tremendous losses as adults. Many, if not most, express some judgement of themselves, something to the effect that their problems are not as important as others’. Although it is true that battling a persistent case of Sunday night anxiety or Monday morning depression is a less severe problem than post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from childhood sexual abuse, the consequences are just as real.

Here is something else to consider when you find yourself comparing your problems with others’: a fear manifesting as a low-intensity but chronic anxiety is probably only the tip of the iceberg. With exploration, that Sunday anxiety or Monday depression usually leads to deeper fears about who you are, what you are doing with your life, and even the ultimate meaning of life. If you judge yourself too quickly, you may interfere with an opportunity to discover those bigger fears beneath the consistent worry for which you have built a tolerance. Using our acronym map, once we are facing a fear, the next important step is to explore it. It is part of my job to be sure we dive beneath the surface, so we can genuinely heal from the inside out, rather than slap one more Band-Aid on a broken leg.

I use a simple technique to help people quickly discover their bigger fears. It’s a real time-saver. I call it “climbing down the ladder”; as you will see, a simple succession of sentence completions forms the rungs to the ladder. Here is how it works.

I asked Matthew, who was expressing his fear about pursuing a change of careers, “What are you afraid of?” Matthew answered, “I’m afraid of failing, especially since I would be giving up a successful and stable career to do this.”

I bring out the ladder so Matthew can climb down and discover more about his fear. “I want you to respond with the first thoughts that come to your mind: If I change careers and fail, then…”

“…I will feel terrible,” Matthew says.

I guide him to the next rung: “If I fail and feel terrible…”

“…my wife will never forgive me.”

“If my wife never forgives me…”

“…I will lose her.”

“If I lose my wife…”

“…I’ll be alone.” Matthew’s shoulders drop, his eyes are downcast; he is feeling his “aloneness.” His defeated body language tells me that this is a big one.

I continue. “If I am alone…”

Matthew pauses. I can almost see the emotion beginning to fill him. He speaks more slowly. “If I am alone…” his shoulders drop even more, “I am nothing.”

I decide to take him down one more rung. “If I am nothing…”

“…my whole life will be wasted.”

Using the “ladder,” Matthew and I can continue and no doubt discover even more about his fear, but at this point we have plenty to work with.

Matthew is forty-five years old, a successful human resource director for a fairly large company who was thinking about opening his own consulting and training business, specializing in conflict resolution. He is a thorough, even a little compulsive, man who has already done his homework—including lining up potential customers for his new business—regarding this career move. There is of course natural fear about making the change, but the fear that is getting in his way is the neurotic fear, the Bully.

Matthew is becoming paralyzed not by the understandable fear that his new business could fail, but by the much louder, much stronger fears that his new business will fail, that his wife will then leave him, that he will be alone, and that his entire life will have been wasted. Now those are some big fears. Can you distinguish the Ally from the Bully in this situation?

By using the “ladder” we put the first two letters of our acronym map into play: face it, explore it.

Sometime when you are feeling stuck or confused, ask yourself, “What am I afraid of?” Listen for the first answer that occurs to you, and then climb down your own ladder.

Don’t run from the fear; turn to face it; go looking for the most powerful, threatening part of the fear by climbing down your ladder. The chances of solving a problem are greatly enhanced by accurately defining the problem. Fear of a failed business and fear of an entire life wasted are two very different problems. With the accurate information—the truth about Matthew’s fear—Matthew and I were able to use the next two letters in our acronym map to free him to make decisions based on his business intelligence and his true desires.

When you identify and keep moving toward neurotic fears, you accomplish two things. First, you minimise the chances of a successful surprise attack from the Bully, since you are keeping the light of awareness shining on his scowling face. And, second, you reduce the Bully’s credibility when you step forward, look him squarely in the eye, and say, “Okay, you have my full attention. Tell me again about all the bad stuff that is going to happen to me if I don’t listen to you. Be sure to make it sound real scary.”

Matthew’s story is a good example of knowing when the best strategy is to look straight through our fears, challenge their credibility, and allow our diminishing belief in them to destroy their power over us.

Accepting our fears

Several years ago in a therapy group in which I was a client, I was talking about what I call the “principal’s office syndrome,” that feeling of dread that comes over me whenever I’m told that someone needs to “talk to me later.”

I have since discovered that many people share this experience, but on that day during group therapy my feeling was that I was very alone.

Jacquie, the group facilitator, asked me to describe the feeling of dread in more detail. “Where do you feel it in your body?” she asked. “In the pit of my stomach,” I said. “And in my throat. It’s as if I’m going to either choke or throw up.”

Jacquie stayed right with me. “Close your eyes and tell me where you see yourself. Try not to think about it. Just observe, and tell me what you discover.” The exploration began.

With my eyes closed, continuing to feel what was becoming pain in my stomach and the increasing tightness in my throat, I was transported instantly back in time. “I am in the third grade. I remember my teacher that year because I had a crush on her: Mrs. Scuddy.” I laughed. Scuddy did not seem like such an attractive name, I thought.

“Are you in Mrs. Scuddy’s class right now, when you feel your stomach and your throat?” Jacquie asked.

I wasn’t sure of the answer to her question. “It’s like the answer is both—yes and no. That can’t be…” “Sure it can,” Jacquie gently interrupted. “Just tell me where you are when you tune into the pit of your stomach and the choke in your throat.”

Then I remembered what had happened. The morning bell had rung, and I was late for class. I started running up the stairs. The school principal, Mr. Simmons, called to me, “Young man!” I stopped dead in my tracks and turned around slowly. Mr. Simmons was a mean-looking man.

That’s how I remembered him that day in therapy, and that is how I remember him now as I write this. Mr. Simmons called me to him. He was standing just outside the door to his office. As I walked toward him, he asked me if I remembered his recent announcement about not running in the halls. I, of course, admitted that I did remember.

He pointed to a specific spot in the big hallway, just to the right of that door, and said, “You wait right here. I will be back in a few minutes.” He was stern—no, he was mean and scary. I was eight years old, with terror in the pit of my stomach, and I felt as if I was going to throw up.

I remember Mr. Simmons walking away, down the hall and into another room. Then I was alone. Just me in that great big hallway, standing on the exact spot Mr. Simmons had assigned me. I stared at the doorway he had disappeared into. Then I turned my head and looked at the broad stairs, the steps that led to my third-grade class, and to Mrs. Scuddy. I have no idea how many times I looked back and forth between that doorway and those stairs or how long I remained there in that paralyzed state. I do know what I was thinking, though. I was measuring my chances of a getaway. If I could just get up those stairs and into my class, I felt sure I would be safe. There were so many classrooms and so many children in that building, after all. It would be virtually impossible for Mr. Simmons to find me.

I made my decision. I ran for it. I was already in trouble for running in the halls, but now I had to run as fast as I possibly could. I had to make it to the stairs, all the way up the stairs, and out of sight before Mr. Simmons reemerged from that doorway. I ran fast.

My classmates were still milling around, many out of their seats, when I got there, so it was not obvious I was arriving late. I quickly tried to blend in, also trying to conceal the fact that I was out of breath from my sprint up the stairs. I took my seat and pretended to review some spelling words that would be on a test later in the morning.

Just as I was beginning to feel relief, I looked up from my spelling words to see Mr. Simmons standing in the doorway. He was scanning the room, searching for me. I sunk low in my seat with my spelling list in front of my face in a futile attempt to avoid being caught. But of course he saw me. He crooked his finger toward himself, quietly reining me in. I cannot remember if Mrs. Scuddy was aware of this or not, but I do know that Mr. Simmons and I went back to his office alone, just the two of us.

“What happened in Mr. Simmons’s office?” Jacquie asked.

“I sat there while he wrote my name in a little black notebook of his,” I said. “He made it into such a big deal, definitely playing it over the top, enjoying his power over this little third grader.” I could feel the anger begin to build as I described the scene to Jacquie.

I don’t remember if he brought up the subject of paddling or I just thought on my own of the rumors I had heard about Mr. Simmons’s “electric paddle,” which of course did not exist. I do remember that once I was back in my classroom, I felt as though everyone was staring at me and thinking bad things about me. I was certain that Mrs. Scuddy, my beautiful third-grade teacher, would be disappointed in me.

As I related this story to Jacquie and the group, the feelings in my gut and in my throat increased. Jacquie then helped me to create an imaginary scene in which I was able to travel back in time as an adult to protect my terrified third-grade self. Once I was able to feel the safety that the adult presence provided, the feelings in my gut and throat began to fly out of me. I screamed louder than I thought possible, and tears poured down my cheeks. I slammed my arms and fists into some big, safe pillows, as a combination of terror and rage continued to gush out. The group members gathered around close to support me. My third-grade self was no longer alone in that terrifying situation. Gradually the discomfort in the pit of my stomach dissolved and my throat became relaxed and open.

The emotions that were created when Mr. Simmons caught me running in the hall did not find expression at the time of the event. The event occurred in 1962, but as I identified the source of my discomfort by telling the story in group therapy, the emotions did not exist in 1962. Those emotions were with me in that present moment. I felt that little eight-year-old boy’s unexpressed terror in the present moment.

This is the often painful work of acceptance, the third letter of our acronym map. When the blinders and the blindfolds are off, the emotions we discover must be felt if they are to be expressed. Once those stored emotions are expressed, however, they are gone.

Consider the emotions that may be stuck within you, the feelings still unexpressed. Be aware of the feelings. Resist the temptation to run, and resist the temptation to try changing whatever emotions you discover. Feel what is there to feel. Accept this as your experience, remembering that acceptance doesn’t mean you like it; it only means you know that this is yours to experience.

Fully aware of these unexpressed feelings stuck somewhere inside you, try this strange little exercise: imagine that you, as an adult, can travel back in time, scoop up the child you once were, and walk right through the feelings. Repeat the motto to yourself: NO FEAR. Holding your child close to you, walk straight through the feelings, never changing one of them. Sadness, anger, hurt, shame, confusion—and all kinds of fear. Keep walking until you come all the way through.

The bad news—or what we think is bad news—is that we cannot change the feelings that are already inside us. The good news is that we don’t have to change even one of them in order to heal. We simply have to become willing, with our eyes wide open, to walk straight through them. Acceptance is the way through to the other side of your fears, where you will learn to respond from a position of power and strength.

Responding to our fears

To get to know your fear, you must learn to stand in its presence. Practice standing in the presence of fear, doing absolutely nothing more than being aware and awake.

In the workshop, we begin the afternoon session with a visualization called “The Wall.” It is an exercise in guided imagery to help make tangible the experience of standing in the presence of resistance and fear. The language of “The Wall” is a series of questions…. Imagine yourself standing in front of a big brick wall. Just you and the wall. How close do you stand? And what do you feel when you are facing the wall?

Everyone has a wall—at least one. The wall is a simple and clear metaphor for whatever ails us. It is wise to consider the work of facing our walls as the essence of life, rather than a distraction from life.

Your wall is made of bricks—individual bricks. And the mortar is made of—you guessed it—fear.

Think about it. If we weaken the mortar, if we interfere with the stability of this fear-based substance, the bricks in the wall pose not much more of an obstacle than a house of cards. How do we weaken the fears? The answer is that we move directly toward them. The strongest fears are the unexamined fears. Like vampires, our fears do not fare well in the bright light of day. Another Nutshell on my office wall reads: “Always move toward your demons; they take their power from your retreat.”

I demonstrate this with clients and workshop participants. I did this the other day in a workshop with a woman named Dorothy. As I did my best to melt into the back of my chair, I asked Dorothy to describe her experience. “I feel powerful,” Dorothy said. I asked her, “Right here, right now, who is in charge?”

“I am,” Dorothy said.

Next I had Dorothy, in her forward-leaning position. I reminded Dorothy to remain “in charge” by holding her physical position of leaning toward me, instructing her to read from an index card I handed her:

“Thom, you are pitiful. There is no way you will succeed, no matter what you say or what you do. The only thing you will succeed at is making a fool of yourself. You are a loser. You have always been and always will be a loser. Give it up. The only chance you have is keeping a low profile. If you’re lucky, maybe people won’t notice you.”

After Dorothy had read the card to me twice, I sat quietly for a few moments, allowing everyone in the room to experience the heavy feeling that seems to literally hang in the air in the wake of such negative, condemning statements.

Then I asked her again, “Who is in charge here?” “I am.” As is usually the case with this exercise, Dorothy could feel the power that came with her position. “You are in charge. That’s right. Do you know why? What about our little experiment puts you in charge?”

“I suppose it is my body language, and the negative things I said to you. I am in charge because I am sitting up, leaning forward, and criticizing you,” Dorothy said with increasing confidence.

Abruptly I sat forward, moved to the very edge of my chair, interlaced my fingers, and put my forearms on my knees. I had moved suddenly to a face-to-face position with Dorothy, my nose no more than six inches from hers.

“Wrong,” I said. “What put you in charge before was not your leaning forward; it was my leaning back. And now,” I said with deliberate sternness, “you are no longer in charge, are you?”

Dorothy was silent, and then with a not so powerful voice she said, “No.”

When Dorothy directed the personal threats at me and I moved forward, literally leaning into them, I was demonstrating an important first step into the final letter of our acronym map, responding. My life and my work have taught me that freedom from fear has nothing to do with being rid of fear, and everything to do with making conscious, healthy choices about how we will respond in the presence of fear.

Freedom at last!

Fear loves judgement, and there is nothing more efficient at plopping us right back into the mainstream traffic as judgement. Fear uses judgement like a carpenter uses a hammer. Consider how it works: We are afraid of what others will think of us—some we know, many we have not yet met, and even more whom we will never meet. We are afraid of individuals and collections of individuals; their potential criticism terrifies us. But we criticize and condemn those very same people because we think the best defense is a good offense. We judge them to distract ourselves from our fear of them. “You are stupid [or silly, naive, unscrupulous, incompetent, a little off the mark, or evil incarnate]” is easier to think than, “I am afraid of you.”

There is no doubt that fear fuels judgement. It always has, and it always will. The only choices we have are whether we will believe what fear tells us and whether we will think, feel, and do as it instructs. “Hurry, hide underneath that table,” my fear might tell me, and without giving it a second thought [this entire process is about learning to have second thoughts] I am beneath the table, with my head down.

Duck and cover I believe we used to call it. Learning to recognize the distinctive voice of neurotic fear, the Bully, when it speaks, so that we can disagree or at least disobey, is a lesson that lines the roads less travelled.

Using the simple metaphor of fear’s two voices, the Ally and the Bully, may not seem like much when someone first encounters it, but the potential impact of this practice cannot be underestimated. Learning to perceive our relationship with fear rather than just having the experience of fear has the power to transform our lives.

We do have a right to live beyond fear’s control, but with that right comes the responsibility to face, explore, accept, and respond consciously and proactively to the truth that we will discover when we do not run away. These roads are less traveled because they are difficult roads along which we will be repeatedly confronted with the simple human fear of stepping outside our own comfort zone. Whether that means standing up consistently to the Bully within us, or speaking the truth in our marriages, or traveling back through time to rescue ourselves from abusive circumstances, it must be done. How else will we learn?

My good friend Evelyn Barkley Stewart, author of Life with the Panic Monster, says that when we give voice to our fears—tell the truth about our vulnerabilities—we are instantly less likely to be acting out of fear. Evelyn inspired this Nutshell: “Tell on your fears. It’s the appropriate use of tattling.”

To practice the NO FEAR motto recommended by the wise little voice in my head, I must speak up. It will not do for me to keep who I am a secret from the rest of the world. The big challenge for me, and for you, is to represent ourselves well, to learn all about who we want to be, and then go out there and be that person to the very best of our inherently imperfect abilities.

The If-Then technique

Make a list of specific fears in any given situation, and then you address each fear, one at a time, by pretending that it has actually happened. In response to each fear, create a specific plan for how you will respond in a healthy and productive manner. For example, if the fear is losing your job, then make a plan for what to do when you lose your job: “If I lose my job, it will hurt and be very scary, but I don’t have to panic. I have a list of friends and associates who will be willing to help me find employment. I might even find a better job.”

For obvious reasons this technique has been criticized as being negative and counterproductive. And it would be if the fear scenario becomes the focal point. The opposite is intended, however. By making a realistic and specific plan to deal effectively with each fear on the list, we free ourselves from having to pay attention to the internal threatening, “You’re going to be sorry” messages.

Fear says, “If you do what this idiot, Rutledge, tells you, you will surely lose your job, and your husband will leave you.”

You of course feel the tug in your gut, for these are important elements in your life, but to the fear you respond, “I don’t think so, but if so, I have made plans to handle the fallout.”

Thom’s Nutshells

- Self-Saboteur’s Motto: you cannot lose what you do not have.

- Heart and mind work best as equal partners.

- All things in turmoil in and around you are evidence that you are still alive.

- Growth always moves from the inside out.

- Courage is to fear as light is to darkness.

- The human condition is one of chronic forgetfulness.

- The difference between knowledge and wisdom is experience.

- To be addicted to control is to be endlessly out of control.

- Hope and fear are traveling companions.

- Don’t waste your dissatisfaction; use it as fuel.

- Humility is the awareness that I am neither better nor worse than anyone else.

- Arrogance can only exist where genuine self-love does not.

- God flunks no one, but he sure does give lots of retests.

- Hear with your ears, rather than your fears.

- Seek simplicity. Simplicity works.

- Victims believe how they are doing is determined by what happens to them; nonvictims believe how they are doing is determined by how they respond to what happens to them.

- I reserve the right to disagree with myself.

- Measure strength according to willingness instead of willpower.

- Forget about finding the right answers; just make a list of some very good questions.

- I think uncertainty is the nature of life…but I can’t be sure.

- Be in charge of your life. Forget about being in control.

- Always move toward your demons; they take their power from your retreat.

- Don’t let your insights live with you rent free. Put them to work.

- Fear is sometimes wisdom and sometimes folly.

- Blame is a good place to visit; you just don’t want to live there.

- Tell on your fears. It’s the appropriate use of tattling.

- We all talk to ourselves; we just need to get better at it.

- It’s not the thought that counts; it’s your relationship to the thought.

- Everything is relationship.

- Continual fear of making a mistake is a terrible mistake.

P.S. To maintain sanctity of the source, this article follows American English.

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!