I may look old, and act old, but I’ll always be a baby—to my parents. That’s one thing that will never change. 16 months separates myself from my middle sister, and another 23 months lie between my middle and oldest sisters.

No matter what their position in the family lineage, everyone has qualms about where they fall in the order of things. For the oldest, it’s having the strictest rules, for the middle child, it’s the desperate fight for attention, and for the youngest, it’s the dreaded hand-me-downs that make life seem so unfair.

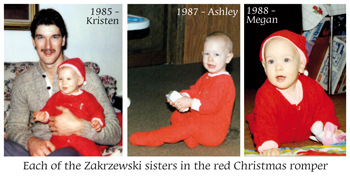

Baby in red

You need to only flip through the pages of a Zakrzewski family photo album to find evidence of various examples of the ‘third-hand’ clothing I speak of. What appears at first glance to be different poses of the same baby dressed on Christmas day is actually a set of three separate photos taken across the years of each sister in the same terrycloth pyjama suit with booties and a matching red cap. Though it may seem cute to any outsider, this agonising wardrobe repetition wore on as the years continued, making me feel just a bit less colourful and wee less fortunate than the rest. I found it extremely difficult to express myself wearing the clothes that I did not, in fact, select off the store shelves.

Nevertheless, I had a happy childhood and understood the struggles of my parents to provide their daughters with nothing but the best. I accepted my lack of personal expression and, as time passed, quickly realised the reasons for their thriftiness. My father worked plenty of long hours to ensure my mom could stay at home with his girls. And that she did: for 12 years.

The short end of the stick

Being the youngest was a double-edged sword in many ways, I learned from my sisters’ mistakes, but as the last of three, I barely received a pat on the back for succeeding in anything remotely major. Being inducted into academic honour societies, making the varsity basketball team, or passing my driver’s test, nothing earned me much attention because it had all been done before.

Being the youngest was a double-edged sword in many ways, I learned from my sisters’ mistakes, but as the last of three, I barely received a pat on the back for succeeding in anything remotely major. Being inducted into academic honour societies, making the varsity basketball team, or passing my driver’s test, nothing earned me much attention because it had all been done before.

To make up for lost ground, I did my best to achieve everything above and beyond what they had already accomplished. I spent extra hours studying in high school and college, doubled my efforts practising sports, and pitched in more around the house. Sometimes, it paid off—literally [on the sly, my mom would slip me an extra five dollars allowance each week for doing additional chores]—but most times it went completely unnoticed.

Battle for number one

Now that we’re adults, the pressure is on, more than ever, to be my parents’ favourite. Although none of us will admit it, each of us feels a tinge of jealousy when the other is praised, rewarded or acknowledged for her efforts—typical sibling rivalry.

For his own amusement, my father plays into this competition. When one of us gets even an inch ahead in his book—whether for mowing the lawn, grabbing him a drink or giving an unsolicited hug—he playfully teases the others, claiming that daughter will receive 34 per cent of his will.

I give credit to my dad for sharing the same house with four females for a whopping 25 years. In the afternoons and on weekends, I felt it was my daughterly duty to fulfil the role of a son by playing catch, helping with physical housework, going on fishing trips and more. It’s the most I could do for a man who sacrificed so much to give me the things he didn’t always have while he was growing up.

The reality

Whether I get that extra one per cent or not for my efforts—mind you, I couldn’t care less. Either way—I guess I have to admit it’s not all that bad being the baby. Growing up, how else would I have convinced my parents to slightly bend the rules—like letting me stay out one hour past curfew—and who else’s mistakes and triumphs would I have learned from?

Sure, being the ‘runt’ of the ‘litter’ had its downsides, like constantly being picked on and compared to the girls who came before me both in school and at home, but things could have been worse. At the end of the day, I could have no siblings at all. Then where would I be? I’d still be the baby, but I wouldn’t have someone else’s faults to learn from, someone else to talk to when lonely, and most importantly, I wouldn’t have the satisfaction of competing for the title of ‘favourite’. And—I almost forgot—if it weren’t for me, the middle child would no longer have an opportunity to whine about being the middle child!

In the long run, while I may be the tallest, I’ll always be at the bottom of the totem pole… and that’s right where I want to be.

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!