Sacred items are wonderful. They cross all boundaries of race, religion, faith, or language; they draw the curious attention of those who have their own and hold them dear; they create an instant bond of the familiar, a shared secret acknowledged in subtle gestures, momentary eye contact, a written confessional. Rosary, japa beads, a yoga mat, a river, a mountain, a temple, mosque, or church: whatever shape it takes, it is in itself a form of divine yoga, a linking with the supreme through the tangible components that connect us.

I live in Mayapur, on the banks of the Ganges. The village and the river alongside are themselves sacred: the depth of life, activity, thought, and purpose are tangible in an environment like this, where the sound of temple bells fills the air, where mantras and song, music and rhythm, prayer and meditation, are all daily practices. In the peaceful early morning, I like to sit with the sounds of an Indian temple village waking to life around me, while I chant mantras—words that embed themselves in the soft surface of morning and which leave an imprint that remains throughout the day, sustaining me until night falls. In Sanskrit these things are called samskaras, which literally means ‘impressions’.

From birth, we have impressions placed in our minds through sensory perception—little scars that mould us, that shape our thoughts and actions, our characters and traits, our quirks and idiosyncrasies, our strengths and weaknesses, our fears and habits, our loves and hates. They might appear to us now as childhood memories—innocuous or harmful—but they have left their mark on our psyche. They are impressions created by the actions and words of those around us when we were very little, and later by ourselves.

So it is with sacred rituals

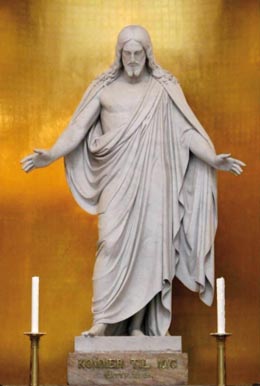

Statue of Christ, by Thorvaldsen, Vor Frue Kirke, Copenhagen

Statue of Christ, by Thorvaldsen, Vor Frue Kirke, CopenhagenThey’re not simply habits or mindless acts passed down from generation to generation: they are the ingredients which, when combined, become the art of making life sacred. They cleanse the consciousness and prepare the mind for what lies ahead. They set up roadblocks and act as traffic police, redirecting the overflow into a side culvert where they wilt rapidly, abandoned in the desert of unwanted thoughts and deeds. Sacred chanting, prayer, and meditation create an impression, a spiritual mechanism that deflects the material energy. It’s my armour, my bodyguard, my sanctuary, my soft armchair, my closest friend, my confidante, my sustenance, my drug of choice.

What a beautiful gift to be able to touch a smooth, oft-handled string of prayer beads, the cool wood polished by years of touch and meditation; to pick up a book whose words of wisdom etch themselves in the heart and mind; to listen to a hymn, a chant; to enter a sacred space of a place of worship—whatever the flavour—and feel your place, even if it is as a visitor. We don’t have to be a practitioner of a particular form of faith to find inspiration in its roots, its sacredness. The familiar, haunting, yet beautiful sound of an adhan [Islamic call to prayer] breaking into the air during the rush of Calcutta’s midday chaos still pulls the heartstrings, reminding one to pray, to remember, to stop, to honour the Divine, in whatever way is dear to us.

I was in Copenhagen, my husband’s home town, some years ago, and there, in the Church of Our Lady in the centre of town, it was Thorvaldsen’s statue of Christ above the altar that captivated me. With his arms extended in a welcoming gesture, this huge, 25ft white alabaster carving reminiscent of Canovo’s delicate renderings—a strong influence for Thorvaldsen—dominates the entire church. From the massive vaulted entry hall, past similar but smaller statues of the 12 apostles, along a seemingly never-ending aisle to the pulpit, the figure drew me in. The stigmatas are visible at close range, but so discretely executed that they are secondary in the figure that captures first the man, and then the Christ. His head is bowed; his eyes fall upon whoever stands before him. Carved into the base at his feet are the words “Come to me”, echoing the mood of his extended embrace. The words are taken from Matthew 11.28: “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.”

Definitely a sacred space. I’m not a Christian, and a church is not my space of choice, but it was a sacred moment, nonetheless. Powerful, if we’re open to it, whatever the flavour. What’s your sacred space?

This was first published in the November 2013 issue of Complete Wellbeing.

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!

Spot an error in this article? A typo maybe? Or an incorrect source? Let us know!